Let Our Statues Speak

Let Our Statues Speak is a multi-part, collaborative project, which began in September 2018.

Instigated to spark a wide-ranging investigation into public space, and to generate collective conversation around the commemorative statues found in our civic spaces. Not in an effort to remove them, but to surface the complex, and often conflicted stories, that lie unexamined within their forms. To let these statues speak.

‘A shared national identity … depends on the cultural meanings which bind each member individually into the larger national story… The National Heritage is a powerful source of such [cultural] meanings. It follows that those who cannot see themselves reflected in its mirror cannot properly ‘belong’.’ – Stuart Hall

The Stuart Hall Foundation will co-create workshops, residencies, commissions and publications through an ongoing series of partnerships and artistic collaborations.

Let Our Statues Speak will intervene in the urgent, Brexit-triggered national conversation over who gets to call Britain home, and collectively shape a debate on the cultural construction of ‘Britishness’ that is compelling and expansive enough to embrace multiple allegiances and entangled histories. Over time, all of this will be gathered here as part of our growing digital resource.

Memorials to the future, reflecting the past

In Silent Empress (2012), a public commission for Yorkshire Sculpture Park in Wakefield, the artist Sophie Ernst attached a sound tag to a public statue of Queen Victoria. The sound was a monologue emanating from a megaphone temporarily positioned in front of the statue’s face. Comprising quotes from the journals and letters of Queen Victoria, and extracts from speeches and texts by past Prime Ministers, it gestured towards an apology for Britain’s colonial past. The statue spoke for 30 minutes before Wakefield Council decided it was ‘disrespectful’ and needed to come down.

The outbreak of public protests over commemorative statues – from Charlottesville to Cape Town to Oxford – evidence a shared truth: the past is contested terrain. National histories are not national facts. The nation is an ‘imagined community’ – a cultural construct.

There is a need for us to collectively address the paucity of cultural narratives that directly engage our myths of origin.

Past Events

Artist’s Residency with Serpentine Galleries

In spring 2019 the Stuart Hall Foundation began a collaboration with Serpentine Galleries as part of Let Our Statues Speak. The artist’s residency, hosted at the Serpentine, connected the complex and multiple histories of the public statues surrounding the Serpentine and throughout Hyde Park, with the neighbouring communities.

_

Workshop: University of Manchester

25 February 2019

This second workshop with invited participants across academia, arts, culture and activism focused on the role of our education systems, exploring the possibility to work with cultural institutions and schools to engage in conversations on difficult histories around public statues, buildings and signage.

Read Report: Statues and Pedagogy

_

Paul Mellon Centre: British Art in the Age of Empire 2.0

4 February 2019

This roundtable workshop, organised in collaboration with Tim Barringer (Yale University) and Hammad Nasar (Director of the Stuart Hall Foundation and Senior Research Fellow, PMC), gathered a group of people who have actively sought to demonstrate that empire belongs at the centre, rather than at the margins, of British art and culture. Participants asked: within the context of national and international debates about the impact of Brexit, the global role of Britain, and what has been dubbed as an attitude of “Empire 2.0”, what of art and empire now? Does empire still haunt histories and exhibitions of British art rather than inhabit them?

Read Report: British Art in Age of Empire 2.0

_

Workshop: University of Westminster

22 September 2018

Let Our Statues Speak launched with a first workshop at the University of Westminster with 16 participants including artists including Naeem Mohaiemen, Erika Tan and Sophie Ernst; academics and cultural activists such as Roshini Kempadoo, and curators; including Kate Jesson, Manchester Art Gallery. This workshop sparked new conversations and possible collaborations centred on statues across the UK.

ERIKA TAN let our statues speak 2018.pdf

Apology and ‘Eingedenken’ by Sophie Ernst 2018.pdf

Research and development for Let Our Statues Speak is being realised with Art Fund Support

Related

"The challenge of the 21st century would be "how to live with difference""

"The challenge of the 21st century would be "how to live with difference""

16th March 2020 / Article

Haitian immigrant artists in Brazil

By: Caetano Maschio Santos

The challenge of the 21st century would be "how to live with difference"

"The challenge of the 21st century would be "how to live with difference""

Diasporic Negotiations of Belonging and Citizenship, Cosmopolitanism from Below and the Political Aesthetics of Migration

By Caetano Maschio Santos

caetano.santos@merton.ox.ac.uk

Introduction

Echoing W.E.B. Dubois, Stuart Hall once said that the fundamental challenge of the 21st century would be “how to live with difference”. In this brief excursion through parts of my work with the Haitian diaspora in Brazil, I’ll try to showcase how music making provides us with valuable insights to reflect on how this specific black migration wave has spurred processes of negotiation and construction of cultural identities, and is struggling to be recognized as a legitimate part of Brazilian society. In the processes of creating its own spaces and pathways for political action, we find complex entanglements of Hall’s Fateful Triangle: race, ethnicity, and nation.

Haitian immigration to Brazil

Albeit still little known within the Global North, Haitian migration to Brazil has an important place within that which some name as the global “crisis” of migrants and refugees. In the Haitian case, a combination of the longue durée effects of colonialism and imperialism, restrictive immigration policies, internal political crisis (Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s ousting in 2004), international occupation through United Nations’ MINUSTAH mission from 2004 to 2017, and natural catastrophes (the Port-au-Prince 2010 earthquake) has come to affect time-honoured migration routes to the US, Canada and France that stretched back at least to the 1950s, now bent towards South America, specially to Brazil and Chile. Scholars researching Haitian migration to Brazil have linked it to the country’s significant economic growth in the first decade of the millennium, its military presence in Haiti leading MINUSTAH, to Haitians perception of or belief in a cultural affinity between Haiti and Brazil (centred on the sharing of African roots) and to restrictive immigration policies in the Global North (Audebert, 2017).

In the borderline between economic migration and climate refuge, Haitians arriving in Brazil have been granted a special humanitarian visa that affords them right to work and reside, and the possibility of bringing relatives through family reunification processes. Even though a significant percentage of migrants held higher education degrees, the staggering majority ended

up taking very precarious work, becoming cheap labour force, in activities such as civil construction and meat processing. Whilst many have worked their way out of this, one is reminded of Hall’s powerful suggestion on how race is the modality through which classed is lived – something true not only for Haitians but also for Afro-Brazilians even today, more than a century after the abolition of slavery, as income statistics continue to demonstrate the structured racial and gender inequalities in Brazilian society. Last but not least, scholars studying Haitian migration have shown how a racializing gaze has been determinant in forging the native/other divide in Brazil (Uebel, 2015), and a common experience to Haitian migrants has been the sudden confrontation with the fact of their own blackness, underscoring once more the continuing importance of the work of Frantz Fanon.

Music and Migration: Haitian artists in Brazil

As it seems to be the case with most diasporas, with Haitians also came along music, or, shall I say, an overwhelming diversity of Haitian and Caribbean musics: konpa, rap kreyòl, reggae, bachata, reggaeton, merengue, twoubadou, gospel music, etc. Haitian immigrant artists’ music making is a noteworthy grassroots cultural industry, despite still barely visible (and audible), and has gradually increased its output and sophistication, specially during the last 3 years. It is all the more surprising if we stop to consider the intense work routine that most of these artists/workers live on a daily basis, having to find the time to compose and record, the latter mostly carried out in the home studios that they have been setting up through patient savings and collective efforts. Within the remarkable diversity of this diasporic musical output, what I wish to stress here is Haitian artists’ significant engagement with Brazilian reality, a reflexive and dialogic engagement that denotes the work of truly organic intellectuals, in the Gramscian sense, through the commentary, critique and interpretation of their own lived reality in Brazil. It’s the kind of intellectual workings of what Stuart Hall called a diasporic consciousness – of those who have one foot in and one foot out, are both here and there, constantly living in translation and remaking themselves (Hall & Werbner, 2008). Particularly, I’d like to briefly comment on two specific cases to illustrate what I’ve just said.

The first one is the song “Lula livre”, by Surprise69.[1] Surprise69 is a musical group formed by Mariolove, Elnegroflow, and RealBlack, artistic names of three Haitians migrants living in São Paulo. According to them, Surprise69’s main aim is to help Haitian immigrants within and outside Brazil through art, encouraging them to pursue their dreams and vocations. In the final weeks of the 2018 presidential campaign, as right-wing candidate and now president Jair Bolsonaro approached victory, Surprise69 released in social media and Haitian WhatsApp groups a new song and video clip entitled “Lula livre” (Free Lula). Mixing freestyle hip hop verses and a sort of political campaign jingle chorus over a digitalized breakdance beat, the song was an overt manifestation of support for Workers Party (PT) candidate Fernando Haddad, and also a critique of Lula’s questionable imprisonment due to operation Car Wash. As a participant in some of the digital networks of the Haitian diaspora in Brazil, I was then witnessing Haitians’ apparent unease with Bolsonaro’s likely victory, and the compelling critiques they addressed him, facts connected to his openly xenophobic, racist and anti-minority posture. Surprise 69’s song, despite circulating mainly within the circles of the Haitian diaspora, nonetheless succeeded in converting a reading of the political moment into music that sought to enable political action, aligning itself with a powerful tradition of politically engaged music making in Haitian history known as mizik angaje (Averill, 1997), one of the most distinguished marks of cultural resistance against the Duvalier dictatorship. Since as migrants Haitians are dispossessed of the right to vote, Surprise69s’ musical agency can be viewed as manifesting a type of cultural and sonic citizenship, stemming from their own conjunctural reading and using the available means to craft belonging and make themselves heard as politically conscious subjects.

The second case I’d like to address here is overwhelmingly infused with particularities. It concerns the individual articulation of cultural identity through music by Alix Georges, a Haitian migrant living in Brazil’s southernmost state, Rio Grande do Sul. It concerns his strategic use of a popular regional song through lyric quotation in daily conversation and his translation of the song to French.[2] The song, “Canto Alegretense” by the family-based ensemble “Os Fagundes”, refers their native town of Alegrete, close to the border with Argentina and Uruguay, and can be seen to stand as a synecdoche to the state’s hegemonic narrative of cultural identity, one in which discourses surrounding the symbolic figure of the gaúcho (the horse rider and ranch peon of the countryside) have historically invisibilized the state’s black population and culture, and highlighted amongst other things the conflicting qualities of hospitality and defense against foreign invaders (Oliven, 1996). Alix’s development of a personal identification with what is known as “gaúcho regional music” (Lucas, 2000) since his first years living in the state has rendered him able to articulate his belonging in a social and cultural environment significantly marked by the hegemony of Eurocentric and white cultural standards.

The main impulse for his use of the song came from daily intercultural encounters, in which his blackness would be the focus of racializing and othering gazes, epitomized by the question of: “Where are you from?”. In these dialogues framed by what Judith Butler has called “normative schemes of intelligibility” (Butler, 2005), in the crossroads of axis of race, ethnicity and nation, Alix’s answer with the initial lines of the song (“Don’t ask me where Alegrete is, follow the path of your own heart”) resulted in a powerful and effective claim to his right to be and to belong, momentarily disrupting power relations and his own othering as a black migrant through a form of conversational sampling (Roth-Gordon, 2012). He even came up with a hybrid identity moniker to mark the uniqueness of his position: Haitiúcho, a combination of Haitian and gaúcho. The final product of this process, his translated version of the song, achieved considerable popularity within the state, and, as a consequence, got him to know the composers of the song and get their authorization to include it free of copyright charge in his CD. Significantly, he later was invited to Alegrete and awarded the official prize of “Black Star of Alegrete” by the city’s municipal chamber, as part of the celebrations of the Brazilian Black Consciousness day. This second example allows us to see how, through the able use of what is regarded as an authentic asset of regional cultural identity, Alix musically played with identity through difference, effectively countering the binary native/migrant divide. This might be seen as a consequence of his cosmopolitan outlook and engagement with local culture, a cosmopolitanism from below, of those who had little or no choice as to whether become cosmopolitans, as Hall once said (Werbner & Hall, 2008). Amongst other things, then, Alix’s musical agency speaks loudly to Stuart Hall’s comments on cultural identity within the Caribbean diaspora (Hall, 1992): the matter of “becoming” as well as “being”, the unstable points of suture made within practices of representation, within discourses of history and culture – made through a politics of positioning affected by unequal power relations.

Concluding remarks

Despite having had set aside many of the complexities of these examples, in way of conclusion I wish to stress that the black labor migrant wave that characterizes the demographics of Brazil in the last decade, of which Haitians are perhaps the most significant part, has brought to the fore issues of race and identity in a unique way, questioning the hegemonic understanding of racial relations in Brazilian society, still today marked by the ideal of racial democracy, the harmonious interracial model of the three races owed to the thinking of Brazilian anthropologist Gilberto Freyre in the 1930s – consequences that, I might say, I’m not really sure that Freyre would unhesitatingly accept. However, in real life one is confronted by the enactment of a racially marked regime of differentiated citizenship, structurally lived and enforced, both formally and informally, affecting the daily lives of Afro-Brazilians and black migrants such as Haitians. It is in such a context that the musical production of Haitian artists such as Surprise69 and Alix Georges attests to what ethnomusicologist Phillip Bohlman has named the political aesthetics of migration (Bohlman, 2011), and stands out as a significant engaged grassroots musical phenomenon. In a global context of escalating nationalism, authoritarian and conservative right-wing populism, Haitian migrants’ aesthetic agency is providing us with valuable lessons on how to learn to live with difference.

Footnotes

- The song can be viewed at < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTsE7oJIIgo> [16/03/2020].

- Alix’s version can be viewed at < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hRHKvQJQ80I> [16/03/2020].

References

Averill, Gage. A day for the hunter, a day for the prey: popular music and power in Haiti. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Audebert, Cedric. The recent geodynamics of Haitian migration in the Americas: refugees or economic migrants?. Revista Brasileira de Estudos de População. Belo Horizonte, vol. 34, n. 1, jan./abr. 2017, pp. (55-71). Available at: <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbepop/v34n1/0102-3098-rbepop-34-01-00055.pdf>. [04/11/2018]

Bohlman, Phillip. When migration ends, when music ceases. Music and arts in action, vol. 3, issue 3, 2011, pp. (148-165)

Butler, Judith. Giving an Account of Oneself. Ashland, Ohio: Fordham UP, 2005. University Press Scholarship Online.

Hall, Stuart. Cultural identity and the diaspora. In: WILLIAMS, Patrick; CHRISMAN, Laura. Colonial discourse and post-colonial theory: a reader. London, Harverster Wheatsheaf Ed., 1994, 222-237.

Hall, Stuart; WERBNER, Pnina. “Cosmopolitanism, Globalisation and Diaspora”. In: Werbner, Pnina. Anthropology and the New Cosmopolitanism: Rooted, Feminist and Vernacular Perspectives. Oxford: Berg, 2008.

Lucas, Maria Elizabeth. “Gaucho Musical Regionalism”. British Journal of Ethnomusicology 9.1 (2000): 41-60.

Oliven, Ruben George. Tradition Matters: Modern Gaúcho Identity in Brazil. New York: Columbia UP, 1996.

Roth-Gordon, Jennifer. “Linguistic Techniques of the Self: The Intertextual Language of Racial Empowerment in Politically Conscious Brazilian Hip Hop.” Language and Communication, 32.1 (2012): 36-47.

Uebel, Roberto Rodolfo Georg. Analysis of the sociospacial profile of international migration to Rio Grande do Sul in the beginning of the 21st century: networks, actors and scenarios of Haitian and Senegalese immigration. Master thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Geography Graduate Program, Brazil, 2015.

19th July 2022

#ReconstructionWork: Building Black Cultural Institutions

What is the word ‘Black’ in ‘Black Cultural Institutions’? Why does it seem like there are so few black-led arts organisations in the UK that...

"what transformative elements of this world exist for its users?"

"what transformative elements of this world exist for its users?"

8th April 2020 / Article

Offline Responses to an Online World

By: Priya Sharma

what transformative elements of this world exist for its users?

"what transformative elements of this world exist for its users?"

This paper focuses on the current theme of offline response that is the result of research conducted on digital identity work and labour amongst queer and female British South Asian Instagrammers. In this context, online space is defined as internet-based social media platforms and offline space refers to the local diaspora community or family in which the participant is embedded.

This quote from Christine Hine speaks to the complex ways in which we navigate our way through these online and offline spaces:

‘ The internet has brought us together in myriad new ways, but still much of the interpretive work that goes on to embed it into people’s lives is not apparent on the Internet itself, as its users weave together highly individualized and complex patterns of meaning out of these publicly observable threads of interaction.’

(Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied and Everyday)

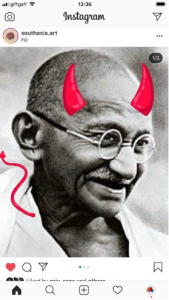

The image above is a screenshot taken from Instagram. It is a doctored image of Gandhi as the devil posted up to an account called SouthAsia Art. This image, along with others on this account are the result of an Indo-Fijian artist’s residency, where she has researched the plight of female South Asian indentured labourers in Fiji and Gandhi’s complicity with the British empire in deciding their fate. The offline conversations and activities that have resulted in this image go some way in highlighting these complex

patterns of meaning that Hine is talking about that aren’t obviously apparent on the internet alone. It would be interesting to gain an insight into the activity being done currently in Fiji around this forgotten history and the meetings and conversations that are taking place amongst the South Asian diaspora there. And it is the uncovering of a working-class female South Asian history, being done by female scholars from the diaspora that is at the heart of the activity behind this image. In this same vein, this research presents an opportunity for young British South Asians who exist outside of male, cis-gendered heteronormativity to reflect on and speak for themselves, about themselves and others who inhabit this online space. Just as the diaspora is recovering its histories, so too should it be allowed to articulate its present.

The decision to analyse participant responses was taken as opposed to analyses of digital content that users put up on their Instagram profiles as a different truth (and albeit one that is rarely researched) was found in participant’s reflections of this digital world. We know that we are beyond the point of the early days of tech utopia and simple empowerment online because the real-world systemic inequalities are perpetuated in the digital world. But what transformative elements of this world exist for its users? What are the limitations and barriers? How could participants explain, in their own words what this world represented to them? And in turn, what would these responses reveal about the wider South Asian diaspora in Britain today?

Thirty years after Stuart Hall’s discussion of ‘new ethnicities’, this paper is an attempt to try and think through the ways in which young female and queer British diaspora communities articulate themselves but also reflect on their digital selves and the issues that are confronted through their responses. Drawing on anonymised interviews conducted with 34 Instagrammers, this study attempts to make visible things that their digital content usually renders invisible.

Instagram is a photo and video sharing smartphone app launched in 2010 that enables an account holder to share content with followers who have chosen to subscribe to their account and vice versa. The particular sphere of Instagram the participants inhabit will be referred to as the South Asian Digital Diaspora space (the SADD space) throughout this paper. It is defined as a networked space that privileges articulations of gender, sexuality and culture through the lens of South Asian diaspora communities.

Many themes and issues were covered by participants in the interviews, but what stood out most were the anxieties and connections that lie behind the accounts within the SADD space. Here are some of the themes that really came to the fore and the ones that will be discussed in this paper:

- The private and public account

- Respectability politics

- Digital space invasion

- Racial neoliberalism

The private and public account

The private and public account theme was a prominent one amongst participants: this is where a user can choose to either make an Instagram account private so when someone clicks onto the account, they can’t see the content and have to put in a request to follow it. It is up to the account holder to grant them access to the content. A public account is open so anyone can view content when they click on the account. One participant talks about having a private account that ends up being infiltrated by what they term a ‘lurking profile’:

“So it’s typically a profile with not many posts at all, they follow more people than they are followed by and there’s often no profile picture and they just lurk and watch people’s stories. One of my friends alerted me coz people were making really homophobic comments about me in WhatsApp chats and I was like ‘oh damn’ I have to be careful. I blocked a lot of people after this and I thought it was a safe space because it was private but apparently it wasn’t. You don’t know whose watching, especially when you’re wanting to further your career and a lot of your art entails themes of queerness, there’s this sense of impending danger that you have lurking somewhere at the back of your mind. I think in one way, while Instagram is good in getting stuff out there, you also expose yourself which is difficult to navigate because you don’t know who’s watching.”

Another participant recently made her profile private after her comments on a photograph of a prominent Muslim Instagrammer sparked some outrage:

“There was an argument going on in somebody else’s comment section, as always! She [this famous instagrammer] wears her headscarf in quite a unique way so you can see a little bit of her hair. Then someone commented, a guy, who clearly didn’t know what he was on about saying ‘this is what fame does to you, you forget your morals, you forget your principles, you don’t wear the hijab correctly’ […] I said ‘that’s funny coming from you coz you’re a male and you don’t know the struggles of covering your hair’ […] he got angry at me and said ‘you don’t wear your hijab properly either’ and at that moment I realised for him to say that he’s seen my pictures on my Instagram […] it made me feel something, unsafe I think […] he’s looking at my photos and using that against me.”

Through these responses, we begin to understand how the public and private functions of the SADD space operate. Trying to articulate the intersections of your identity or defending another person’s can put you at risk. For the first participant, it was an ex-school friend who had created the ‘lurking profile’ – this friend had connections to the participant’s family and so there was risk of the offline world becoming an unsafe space for them. For the second participant, before this negative interaction, her profile had been public for a very long time meaning that the SADD space was where she felt safe. After this interaction, this space became unsafe.

To counter the public profile, private ones are made so there is a secret online life being lived alongside the offline life. This doubling of life isn’t new to those that have grown up in strict, conservative South Asian families, the difference is the detail that goes into this digital life and the constancy of it (you’re always carrying it around with you on your phone), which can create real anxiety for participants. The societal risks that exist within the offline and online South Asian community at large creates a barrier to self-representation for the participants, especially when it comes to issues around gender and sexuality.

Respectability politics

This barrier to self-representation, even when challenged, can remain a barrier, the result being the self-censoring of content. Participants are held up to the politics of respectability in the SAAD space. This participant says:

“I know there’s been cases where my mum’s been like ‘take that down now’ because I’m too exposed, and my mum is very liberal. She’s like ‘your projecting the wrong image out there’ and basically compared me to being a sex worker”

The images we would see on this participant’s profile isn’t how she truly wants to be seen, but how her family will allow her to be seen. What this remark makes visible are these private conversations between parents and offspring that happen behind closed doors and influence the images in the SADD space. Even though this participant describes her mum as very liberal, she tells her daughter that she is projecting the ‘wrong’ image by posting up pictures of herself in what she considers provocative clothing, equating the showing of flesh to sex work, which is very problematic for reasons we don’t have time for today . This participant’s notion of parental liberalism, or her mother’s liberalism, permits her to do things, like wear a short skirt and drink as long as it is done away from the community, that it remains invisible. And that no trace of it exists in the SADD space.

This idea of the ‘wrong image’ is echoed in this participant’s answer:

“I’m not going to say I censor it, but I can very easily choose certain issues that I know spark some kind of outrage within my parents’ communities – I would avoid those deliberately. I’m not gonna talk about my personal life so there’s nothing essentially on my profile that would make people think ‘oh my god, look what your daughter’s doing’. What am I doing? I’m just posting photos, so there’s not really anything wrong that I’m doing.”

This participant subconsciously conflates her personal life with doing something wrong – the personal: i.e: the emotional, the intimate is made to feel wrong in the SADD space, so is best kept invisible.

The SADD space is a space of self-representation that can end up being externally policed by those outside of it, especially when it comes down to articulations of sexuality, gender and lifestyle. One way of making the SADD space safe is to make it private, but even then, as demonstrated earlier, it can be infiltrated. So how can participants navigate these complex online/offline relations with some ease?

Digital space invasion

One participant said that the SADD space gave her the confidence to be more vocal about who is she within her local community:

“I think for the confidence levels and the confidence to be outspoken and political and to kind of take that change and put it back into the community as well. I’ve been able to, rather than living that entirely online, I have been able to take that back out and because I’ve shown that side of myself publicly on the internet, now it’s allowed me to show that person to the people I see in the community who’ve seen it on Instagram.”

There is an awareness that this approach comes with risk of confrontation or worse, but it demonstrates one way that these anxieties can be relieved. This approach comes down to how safe somebody already feels within their offline community.

The popularity of the SADD space goes beyond articulations of self to demonstrate the ways in which participants circumvent the traditional cultural industries, making them space invaders of industries that have historically rejected or compromised the work of British South Asian creatives, as Nirmal Puwar writes:

“As we witness a number of policy initiatives under the banner of ‘diversity’, the ‘guarded’ tolerance in the desire for difference carries in the unspoken small print of assimilation a ‘drive for sameness’. Through these processes the kind of questions that are asked as well as the voices that are amenable to being heard within the regular channels of the art world, academia, or other fields of work, can become seriously stunted.” (Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place, 2004)

This digital invasion of the cultural industries has forcibly opened up a space of difference without compromise and industry gatekeeping. One participant runs her business entirely through the SADD space and has relied on it heavily to gain recognition and get work, promoting herself specifically as a South Asian tattoo artist:

“I used my Instagram as my portfolio when I was looking for tattooing apprenticeships, and I was lucky enough to have found the apprenticeships I had because of Instagram. I used to be an apprentice at the studio I now own and they had offered me a job there because they saw and liked my work on Instagram.”

Participants have stated that they have gotten art and writing commissions, exhibitions, collaborations and job opportunities off the back of the SADD space and they also make a point of supporting each other through it:

“I’ve been able to connect with some really lovely people locally because of it and have been able to show up to events that were exclusively advertised on IG and learn about a lot of underrated hyperlocal culture that I felt needed visibility as well.”

Staying culturally true to yourself, connecting with others like you, not giving in to dominant whiteness and still financially succeeding by way of bypassing traditional gatekeepers is undeniably empowering for members of the SADD space.

Racial neoliberalism

However, it could be argued that this space, as a social media platform could be described as a cultural industry, whereby the processes of cultural production of British South

Asian identity are not without their problems. Under the racial neoliberal address, there is a call for a shift from the politics of representation to a politics of production (Anamik Saha, Race and the Cultural Industries, 2018), the constraints of which appear largely invisible within the SADD space. On a platform like Instagram, you can feel like you are in control of the processes of production behind your self-representation without having to question it further. This is a platform that has approached participants to sell products, that exists on an economy of likes and sponsorship deals and I think to not interrogate these processes of capitalist production further is to do a disservice to Stuart Hall’s conception of a politics of representation – we mustn’t forget the political. When we do, we begin to see the essentialising effects of the neoliberal processes of production, churning out what we believe to be our own truths, as one participant puts it:

“There’s this South Asian monolithic nation project happening out there which I think is something that I’m quite cautious about because I think that growing up in this country, a lot of South Asians, you’re growing up with loads of people from diasporas and to self – exoticise yourself sometimes because it does go to that at points, there is a real risk because with this collective consciousness which is coming about on Instagram, there is a convergence of more niche people into this bigger aesthetic in order to get recognition to be a part of that project.”

The convergence of South Asian religious and ethnic identities within the SADD space (usually Hindu/Punjabi and middle-class), removes the potential for a radical politics of representation, but this essentialism is not lost on some participants who inhabit the SADD space, which is promising.

Conversely, these processes of production are significant to users because the aforementioned religious and patriarchal barriers present much more of an oppression compared to that of capitalist neoliberal processes of production, which offer a type of safety and freedom to allow participants to be honest without major consequence. As recognised by some participants, these neoliberal forms of self-representation do not offer a long-term solution to systemic oppressions, but it also cannot be denied that the SADD space can be an affirming space for many of its users; this positive response from one participant is a reminder that ultimately we are all searching for ways to belong:

“It makes so much difference to know there are also other south Asians living alternative lifestyles, helping and supporting one another. Giving visibility to and sharing content from these accounts is important to me because I’m trying to be the person I needed when I was younger.”

8th May 2023

Festival of Ideas: The Live Archive hosted by Erin James

Join Erin James, the Sussex University Stuart Hall Fellow 2023, and special guests for a radical reimagining of archival research through...

Share this